Dedicated to Sandra Fralin, Jeanne Belfy, Carole C. Birkhead, and all the other women who took on the history of the orchestra in Louisville before me.

In a May 2003 interview with iClassics.com, Matthew Walters explained how working with the Smithsonian Folkways collection prepared him to digitize and re-release the Louisville Orchestra’s First Edition recordings: “The short answer would be how imperative it is to have well-engineered and well-preserved masters, to carefully plot out a reissue plan, and to have the right distributor.” Four years later, the future of the First Edition re-releases was almost nonexistent, just like Walters himself. The label Walters founded to handle the project stopped updating its website by 2006, although release timetables had been removed in January 2004 and were never replaced; even then, the text still said that the schedule would be released in November 2003. The masters that had been used are missing, the original distributor has been subsumed by larger corporations, and all that’s left are a mountain of legal complications.

It sounds like a heist, a con: man convinces orchestra to give him priceless artifacts, $100,000, and the rights to their record label and summarily disappears, never to be seen again. Even the news forgot him; there is no evidence that anyone has ever reported on the loss of First Edition Records or Walters’ disappearance. Because it wasn’t a heist, which leads to much more complicated questions. If Walters wasn’t trying to steal a record label and a legacy, what happened to him? What happened to the masters? And what, if anything, can be done about it?

***

In its heyday, nothing compared to the Louisville Orchestra’s commissioning and recording project. It is unlikely that any subsequent project ever will. The Louisville Orchestra commissioned more works than any other American orchestra between 1910 and 1978, beating the New York Philharmonic by 26. It was the first orchestra to have its own record label. In 1952, Radio Free Europe began broadcasting Louisville recordings behind the Iron Curtain, which was especially remarkable since Radio Free Europe normally used little to no music during broadcasting. Stravinsky, on his 1967 visit to the United States, chose to conduct only in Louisville and Boston, and Louisville was the only city visited not on either coast. Two works commissioned by Louisville won Pulitzer Prizes.

It’s difficult to reconcile this legacy with the common local consciousness that leads people to ask visitors and transplants, “But why here?” In the way that the Humana Festival of New American Plays at Actors Theater brings both new work and acclaim to Louisville theater, the commissioning and recording project put Louisville on the orchestral map. The effort to introduce new compositions locally was often met with resistance and loud complaint; after poor reception of a concert of only new music, one new work was exhibited per concert alongside older, more traditional work as a compromise.

In fact, the commissioning project and the Louisville Orchestra itself almost came to an early end when money ran out in the late 1940s. Finances have always been a major issue for the Louisville Orchestra, and for other orchestras across the country, but Charles Farnsley, who would be elected mayor of Louisville before he could begin a term as President of the Board, had tried an ambitious plan to balance the orchestra’s books. The orchestra’s size would be reduced to 50 musicians, and instead of relying on famous soloists to garner attention, that money would go toward the commissioning of new works from contemporary composers. The commissions would then be recorded for sale to the general public in order supplement income from ticket sales. His election as mayor the following year only increased his ability to champion his radical new plan, including the establishment of the Community Chest to support local arts – an organization which survives today as Louisville’s Fund for the Arts.

The first music director of the Louisville Orchestra, Robert Whitney, was extremely supportive of Farnsley’s vision, and led the orchestra in the premiere of 11 new works in the first twelve years, alongside the regular repertoire of orchestral music and the Making Music educational series he founded that continues to this day. Despite Whitney, Farnsley, and the board’s best efforts, the issue of finances continued to plague the orchestra after World War II. The 1948-1949 season had been far more financially troublesome, ending with a deficit of over $40,000 that was ultimately reconciled through a donation. Program notes written by Whitney in 1967 confuse that season with the monumental performance of William Schuman’s dance concerto Judith, performed with dancer Martha Graham in January 1950, and several sources in the decades since have repeated the story that the orchestra would have canceled the rest of the season and ceased to exist had the concert not been a national success.

Regardless of whether the implication that the rest of the season was about to be canceled due to lack of funds is true, the orchestra played, Graham danced, and thatnight they all were invited to perform Judith at Radio City Music Hall in New York. That one performance did change the course of American music history – the trip to New York brought the $500,000 Rockefeller grant in 1953, which would save the orchestra from its financial trouble, fund 60 new commissions over the next two seasons, and stimulate the commissioning of new orchestral works across the country.

Between 1951 and 1956, Louisville commissioned 88 new works, while all other major orchestras combined commissioned just 30 – nine of which were for the 75th anniversary of the Boston Orchestra and 25th anniversary of the National Symphonic Orchestra. The rate of orchestral commissions country-wide would continue to increase over the next four decades, but no one orchestra would ever commission 30 works in a single season again.

When the Rockefeller money ran out, Louisville’s commissioning rate dropped off, but it would continue recording its commissions alongside older works on its own label, First Editions Records, eventually totaling over 400 works. The orchestra began releasing vinyl LPs in 1948, the year they were introduced by Columbia. One of the LP’s developers, Howard Scott, worked for several decades as a producer for First Editions. Other than a handful of tapes, most of the 20 years of masters he made with Robert Whitney and the Louisville Orchestra have disappeared.

The known remains of First Editions Records are now located at the Anderson Music Library at the University of Louisville. There is no official record of this online, as the collection has not been processed since its acquisition in 2009 for a variety of reasons: it would be incredibly labor intensive; the library can’t play the unlabeled ½” reels to figure out what is on them; and, most of all, the library doesn’t actually own them – the Louisville Orchestra does.

If you ask to see them, a librarian might allow you into the archive room on the third floor, where the reels upon reels of master tapes take up several entire shelving units. The first time I took a look, I was alone and almost got trapped between an empty card catalog and a shelving unit as I tried to decipher the writing on the tape boxes. These copies once belonged to Andrew Kazdin, the producer at First Editions Records toward the end of the label’s recording history. He was known for his incredible ear and dedication to his craft, especially his work with Glen Gould and Columbia Records. Toward the end of his life, he contacted the Louisville Orchestra to give them his copies of the edited masters he’d collected during his tenure in Louisville. Most are stereo work reels, unedited ½” analog tapes on either three or four channels, and their backups. These reels were physically cut and spliced to produce the edited ¼” masters which would be used to create the vinyl LPs that represent the bulk of the First Editions catalog.

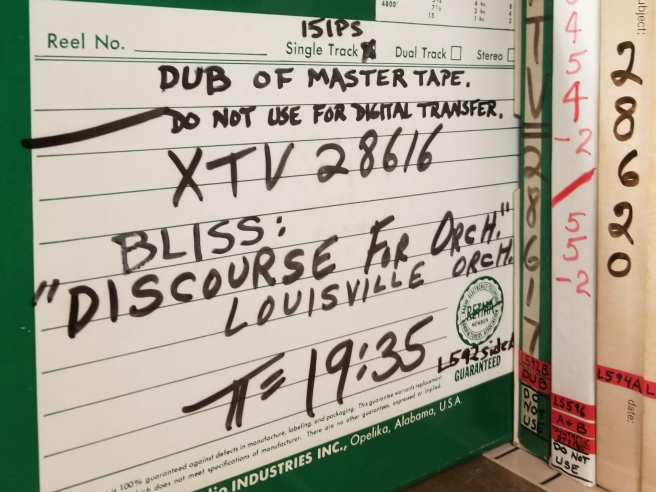

Kazdin’s collection, unfortunately, is incomplete. By the 1976, 30 of the LPs had gone out of print, and some of the original ¼” tape masters were missing. (This is probably due to the fact that Columbia stored its records at Iron Mountain, an underground storage area not unlike our local MegaCavern, and upon retrieval the pressings and masters were disorganized and partially lost.) The Mester records, being more recent and more readily available as well as being the Romantic works he preferred, were re-pressed, and some of the missing tapes were recreated by dubbing un-played LPs to tape masters for the pressings. These dubbed masters would be mostly indiscernible from the originals unless played digitally, explaining why several of the ½” boxes are marked “NOT FOR DIGITAL TRANSFER.”

A small handful of tapes have notes from Howard Scott, but 114 of the 131 commissions were premiered during the first ten years, and many of the Kazdin-era recordings are not of Louisville commissions. And even then, the edited ¼” masters are much more valuable, since they represent the complete, final product of each recorded work as they were intended to be heard.

The rest of the edited tapes remain missing to this day.

There is no physical record of the ¼” master tapes being at either the Anderson Music Library or the UofL Archives and Special Collections (ASC). Several publications reported that they were “at the University of Louisville” during the announcement of the re-recording project initiated by Matt Walters but none specify which library or department. It is unknown whether this was a complete collection, or if the losses of the 70s had already made permanent marks on the First Editions catalog. Walters did ‘borrow’ an unspecified quantity of those tapes from the Music Library around the year 2000, which he used to produce a small handful of CDs reissued under the First Editions name. But like the “five or six” boxes of the Louisville Orchestra administrative records one archivist recalled helping him load into a U-Haul trailer to take to Santa Fe for the re-recording project, none of them were ever returned. In the nearly 20 years since, the papers documenting what he checked out have been lost to time. Matt Walters is the only person who knows the entire truth of what exactly has been lost.

If you want to listen to the First Editions Recordings but don’t want to visit the libraries or hunt down old vinyls or CDs on eBay, you can simply go to any streaming service like Spotify, Pandora, or iHeartRadio and try your luck there. Other than the six CDs gifted to me by a former recording engineer, which were made from the backup session recording tapes and are marked “PERSONAL USE ONLY,” this is the only way I’ve been able to listen to the commissions I’ve spent almost two years learning about. The Spotify collection is surprisingly large, especially given that Spotify did not exist until 2008, several years after Matt Walters disappeared with control of First Editions Records. Many of the album dates make no sense, like the album The Louisville Orchestra Play Frank Martin Concerto for Violin, Cello and Orchestra which was recorded with Robert Whitney conducting but is listed as a 2014 release.

It is unknown how the elusive First Editions recordings ended up online, given the timeline. Some of the later Mester-era releases were on CD, so it’s possible that is the source of some of the albums; iHeartRadio confirmed most of the albums were either distributed by The Orchard (owned by Sony), or IODA (which merged with The Orchard in 2012). But if Walters stopped doing anything for First Editions no later than 2007, how did his CDs come to be online? The First Editions website, resurrected by the Wayback Machine, shows that Walters had partnered with Harmonia Mundi, now a sublabel under PIAS Group, for distribution of the CDs. Neither The Orchard nor PIAS Group responded to emails asking for clarification.

It appears that through multiple acquisitions of multiple distributors, the streaming rights of old First Editions recordings are now in the hands of conglomerate businesses that likely just send out their large acquired catalogs en masse for digital distribution, too big to notice the particular legal mystery behind one orchestra’s music legacy. If there are any royalties to be gained from this, the Louisville Orchestra isn’t getting them.

***

You get a very different picture of Matt Walters depending on who you talk to. Part of the problem is that almost twenty years have passed since he began the reissuing project, and part of the problem is the difference between his previous work and the end result of his Louisville project.

In a 2003 LEO interview Tim King, then-CEO of the Louisville Orchestra, described the situation: “[W]hen Matt came to me, it was a real blessing. He’s doing a quality project, and we get a fixed fee, even if he only sells one disc. If there’s a downside to that, I couldn’t find it. And it’s a very good relationship, too. But so far, to be honest, the best thing is, it doesn’t take staff time, it doesn’t cost us anything and it gets the name back out there.” Walters had worked for Smithsonian Folkways for about a decade; there was no reason to believe that he didn’t have the skills and experience necessary to take on the First Editions catalog. One former colleague from his time at Folkways had little to say about Walters other than that he had done fine work supervising the mastering, manufacture, marketing, and distribution of the label. Even Howard Scott was supportive after Walters reached out to him through colleague Mike Hobson. The CDs that were made were curated, and came with liner notes that help contextualize the music and, occasionally, essays on the composer, and were moderately well-received by the press.

It was only after the re-release project had begun that there red flags began to appear. The former recording engineer I spoke to told me that Walters called him asking about equipment and master tapes. “I determined that his plan was to digitize the ¼” tapes (from which the records had been cut) by playing them on a semi-pro Teac tape machine plugged into his Apple laptop… definitely NOT a professional setup,” he said over email. The engineer credited on the re-release CDs who told me that all he remembered was Walters gave him the tapes, he remastered them, and that was that. A composer and conductor who wrote an essay for one of the CDs described Walters as being a little out of touch with reality, recounting a time where Walters was proposing creating a digital platform for classical music – even though something similar already existed, and when this was pointed out Walters took it as a lack of interest in his idea. Their friendship ended when Walters tried to get him to use his position on an organization’s board to help Walters get a grant whose deadline he’d missed.

At some point around 2004, Walters moved to Austin, Texas with his family, where he likely still lives. Then, or later, it appears he and his wife separated or divorced; ironically, she now works with the Smithsonian, and was not available for comment. Around 2009, the Louisville Orchestra made an attempt to contact him through lawyers in order to recover the tapes and the rights since the agreement had not been fulfilled, but Walters declined. And that was that; there were no additional resources to pursue a man who’d been gone for almost a decade all the way across the country for tapes that no one had the money to do anything with.

It’s tempting, perhaps, to try and assign blame for the Walters failure, but pointing fingers does nothing to help recover the First Editions legacy or help us understand how it came to be. There hadn’t been more than one or two commissions per season since 1969, and recording had stopped around 1995. It must have seemed like there was nothing to lose by letting Walters help. For fifteen or so years after giving away the masters and exclusive rights to the label, through bankruptcy and the recession and strikes, it continued to matter very little, because there was little to be done.

But then: an arts renaissance. When I first started researching the Louisville Orchestra, I was inspired by the coincidence of its transformation under Teddy Abrams happening at the same time as that of Kentucky Shakespeare under Matt Wallace. The Speed Museum was closing for its three year long renovation, and Les Waters and Aldy Milliken had started at Actors Theater and the KMAC Museum, respectively, on the exact same day the year before. The ballet was performing for free in Central Park to Shakespeare; the orchestra was accompanied by DJ Glittertitz. Something had changed, all over the city, and the orchestra was tied up in it in ways I didn’t yet realize.

Then-executive director Andrew Kipe told Arts Louisville that “What we are trying to do is to reclaim the past in a way that is relevant now and in the future. Not because of what we did in the past, but because it’s important work and important to the community.” He was talking about plans for the Orchestra’s upcoming recording project, which would eventually become the record All In, issued under Decca Gold, that topped the classical charts last October and was recently released on vinyl in partnership with Crosley Radio, a Louisville-based company that makes turntables, among other electronics. (You can get a Louisville Orchestra edition turntable through Crosley, which comes decorated with a photo of the entire orchestra.)

Contemporary commission data is unfortunately incomplete, but it seems like Louisville is now keeping up with other orchestras nationwide when it comes to new compositions. The American League of Orchestras archive of world premieres from 2002-2013 suggests that for an actively commissioning orchestra, three or four commissions is significant and five to seven is exceptional. Last season, the Louisville Orchestra premiered “The Greatest,” a tribute to Muhammad Ali, “Heaven + Earth” by Sebastian Chang and set to oil paintings by Vian Sora, and a song cycle collaboration with My Morning Jacket front man Jim James, which will eventually be released for sale to the public. The current season will include a folk opera from Rachel Grimes, and not new music but new artwork from KyCAD artists to accompany the Art and Music spring concert.

Quietly, slowly, “the most interesting orchestra in the world” is reclaiming its past as best it can: new commissions, new recordings, new vinyls. It has shrunk back to its Farnsleyian size of 55 members. There are many differences, of course; commissions these days are more likely to include local musicians of wildly different genres than solicit Pulitzer shortlisters for new compositions. The whirlwind productivity of the Rockefeller years was unsustainable financially and labor-wise in the long term, especially alongside the regular repertoire of concerts and other programs; a few new works per year is more reasonable. The option to buy vinyl is back after being retired in the 1990s, riding the resurgence of vinyl sales that has consistently grown over the last twelve straight years. And, of course, new albums are not under the First Editions name, since Walters still retains exclusive rights.

I’d like to hope for a day where the rights to First Editions Records returns to the Louisville Orchestra again, and funds are found or given or made available to provide a better catalog than streams of dubious origin and ethics on Spotify. This would require a public awareness and demand for the true revival of First Editions’ legacy, and the financial (and legal) means to execute it. In the meantime, I look forward to seeing what new marks on history the Louisville Orchestra makes as it reconciles its past legacy with its current reality.

Special thanks to all those who contributed to my research on this project, especially Daniel Gilliam, Lindsay Valladingham, Nate Koch, Anne Flatte, John Kennedy, Tim King, Robert Birman, Rick Crampton, and so many librarians at both UofL Archives and Special Collections and the Anderson Music Library. Thanks also to Tara Anderson and Micah Peace for your encouragement, and to Sandra Fralin, Carole C. Birkhead, and Jeanne Belfy, again, for paving the way.

For further information on the commissioning and recording history of the LO, plus stuff about Matt Walters, check these out:

The Role of the Louisville Orchestra in Fostering New Music, 1947-1999, Sandra Fralin.

The Commissioning Project of the Louisville Orchestra, Jeanne Belfy.

The History of the Orchestra in Louisville, Carole C. Birkhead

Music Makes a City, Owsley Brown III and Jerome Hiler, and the accompanying webseries about Teddy Abrams, Music Makes a City Now.

First Edition Records website, made available through the Wayback machine.

“Made in America,” interview by Bruce Nixon for LEO (ProPublica link).

“Eight More Miles to Louisville,” re-release review.

Fun Facts:

- Robert Whitney’s only memorial is the plaque outside of Whitney Hall at the Kentucky Center for the Arts, because he donated his body to UofL’s medical school after his death.

- There were actually two separate visits from Soviet conductors during the Cold War: Shostakovich and four others in the 50s, during which Shostakovich was taken, inexplicably, to a cigarette factory, and the visit from Stravinsky in the 60s where he was photographed wearing two pairs of glasses.

- Local TV station WAVE commissioned an entire opera, titled Beatrice, from the LO. The closest library to have a copy is in Georgia, unless a tape of its live TV performance is in a box at the Music Library.

- During WWII, Whitney would recruit various players from Fort Knox, as regular orchestra members would be absent due to the draft.

- The LO premiered a range of ‘challenging’ new music, but one of the more notable ‘firsts’ was first soloist to play the tape recorder for an orchestral work.

- Robert Whitney also worked as a consultant at WUOL, since he had experience in radio and was denied the planned post of Dean of Music at UofL for the LO’s first music director. Eventually, the tapes of LO broadcasts and the In Retrospect series whose creation Whitney orchestrated (ha) wound up back at the Music Library, shelved next to the Kazdin tapes, one floor above where Whitney’s portrait hangs in the stairwell. (Whitney ended up becoming the Music School’s second dean, from 1956-1971.)

- Until fairly late in Jorge Mester’s tenure, all the First Editions recordings, even those not commissioned by the LO, were true to the name and were 20th century works that had never been recorded before. Mester was particularly fond of the Romantics, and contributed the only pre-20th century works to the First Editions catalog.

Emma, I just compiled and posted a “List of First Edition Records releases” on Wikipedia. Apparently nobody had ever compiled it before — at least I couldn’t find one.

LikeLike

Wow, that’s phenomenal! I have one copied from the Birkhead dissertation, but I don’t know of any other publicly accessible lists, and that one is by recording without the release numbers. You’ve done a wonderful service here.

LikeLike

Emma, your article mentions that Spotify has a ton of LOFE releases online for streaming. I count 177 total, including about 133 that were never released on CD! They all carry the “Soundmark” logo on the cover, which was Matt Walters’ company name:

http://www.unsungcomposers.com/forum/index.php?topic=1667.0

So he DID digitize a ton of stuff. He apparently just went out of business before he could release very much of it (the market would be, uh, pretty limited).

Unfortunately, Spotify does not list any catalog numbers (that I could find) and there does not appear to be any way to download anything.

LikeLike

I stand corrected. Spotify Premium for $10/mo. allows downloading.

LikeLike